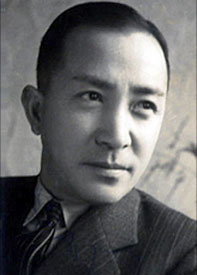

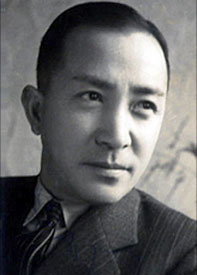

In the 1930s as sound was displacing the benshi live narrators of the silent film houses, the most popular actor of the silent era, Tsumasaburo "Bantsuma" Bando, was at risk of losing his audience.

In the 1930s as sound was displacing the benshi live narrators of the silent film houses, the most popular actor of the silent era, Tsumasaburo "Bantsuma" Bando, was at risk of losing his audience.

His physical acting style conveyed a startling realism that changed the mannered kabukiesque look of earlier films, but in the world of sound, his intensity of emotion needed to be subdued, as it was no longer necessary to convey every feeling with a body posture & expressions alone.

His first talkie was Niino Tsuruchiyo (The Secret of Tsuruchio Niino, Shinko Kinema, 1935), directed by one of the early greats of jidai-geki samurai action films, Daisuke Ito. Had he trusted & listened to Ito, it seems likely his transition to sound would've gone better.

Even a great director was not about to stand up to the Bantsuma as the biggest star of a generation. Bantsuma was accustomed to making every decision himself about his scenes, & had never been wrong so far as the public was concerned.

Ito ended up with a silent film performance that might've worked better without spoken dialogue. Ito ended up with a silent film performance that might've worked better without spoken dialogue.

It was a serious-minded samurai tale with great action scenes such as both Ito & Bantsuma understood well. But Ito had made a transition to sound, & just wasn't bringing Bantsuma along quite well enough.

This inability to believe a director might know better doubtless contributed to Bantsuma's risk of decline. He gave essentially the type of emotive physique-reliant performance he'd given in such unbelievably great films as Orochi (The Serpent, 1925) that had won him unqualified praise.

This time his public wondered if he wasn't after all only a star only for the silent world, & they were more than a little startled to hear that he had a voice more highly pitched than anyone had guessed.

There was nothing odd or squeeky about his voice; he had a great voice for a serious actor. But having developed an image that was regarded the epitome of Japanese manliness, in audience imagination he had the sort of deep baritone as might've boomed forth from a kabuki stage. Instead, he sounded like a regular guy, not an exaggerated hero.

In consequence, his long influential independent film studio was shut down, & he had to contract himself out to Nikkatsu Studio & struggle to regain his audience.

Fortunately he was a massively intelligent man & soon caught on that times had changed. He would trust directors more to know what a talkie needed. And the public, even though at first alarmed that their idol had a high pitched voice, would get used to it. It was a voice that would become an asset when he stopped playing only heroic swordsmen & reached for depths of dramatic films late in his career.

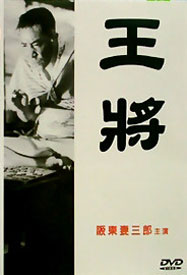

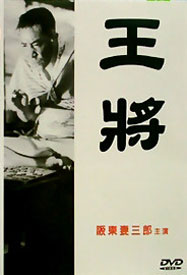

Ito & Bantsuma would score at the apex of film art with Osho, often rendered Oushou (The Shogi King, Daiei, 1948). It is one of the world's great dramatic features, & it amazes me that the least film by Ozu is better known than this tremendous classic.

Ito & Bantsuma would score at the apex of film art with Osho, often rendered Oushou (The Shogi King, Daiei, 1948). It is one of the world's great dramatic features, & it amazes me that the least film by Ozu is better known than this tremendous classic.

It starred a middle-aged Bantsuma, who as a young actor in the sileht era had been famous mostly for noble, nihilistic, or otherwise undefeatable samurai. He had aged & mellowed into the perfect combination of character-actor & leading-man capable of plumbing great depths of beauty & emotion when playing society's social outcasts.

And the director/screenwriter Daisuke Ito had also made his most lasting contribution to cinema beginning in the silent era as one of the first great directors of jidai-geki or samurai films, & continued to make such films right into the 1960s. But here, as in a few other films, he proves himself equally the master of quieter drama, having had a left-leaning sentimentality that permitted him to assess with stunning humanity the condition & the unbreakable dreams of the impoverished.

Along an alley street next to the railroad, Koharu (Mitsuko Mito) struggles to make a home as the suffering wife of an endearing wastrel Sankichi Sakata (Bantsuma). Along an alley street next to the railroad, Koharu (Mitsuko Mito) struggles to make a home as the suffering wife of an endearing wastrel Sankichi Sakata (Bantsuma).

He has never been able to provide well for his family, obsessed as he is with shogi, a chess-like game that he loves to such distraction he invariably fails at his minimal employment.

In a vastly better neighborhood is a man with whom Sankichi has played shogi. He is Master Sekine (Osamu Takizawa), a dignified young seventh-rank shogi champion whom our impoverished hero, officially an amateur, played to a draw. But the judges insisted he "lost" the game because of a rule that does not permit any game to be a draw.

It was not a rule he knew, & even if it is the way it's played at the champion level, he feels Master Sekine has no right to be proud of his "win" when an amateur like Sankichi could not be totally defeated.

His near-success at such a level of play drives Sankichi to pursue professional status, longing for "a revenge match" with Sekine. "Remember it!" he demands of Sekine, though close to tears.

He is changed by the encounter. He decides to stop being a slacker & work hard for his family. But at the same time he wants to study shogi with ferocity, to become an undefeatable master. He is changed by the encounter. He decides to stop being a slacker & work hard for his family. But at the same time he wants to study shogi with ferocity, to become an undefeatable master.

In it's own way this is very samurai-like, though as a member of the underclass it's presumptuous of Sankichi to believe he could become number one anything. In that unboastful presumption lurks the real beauty of his humanity, faith, & heroism.

A film of the lower classes set in the immediate post-war era, showing the privation of the time, Osho treads a careful line between cinema verite & romanticism.

Set largely in an alley on a set as grimy as in Kurosawa's The Lower Depths (Donzoku, 1957), the sorrows & tragedies reveal not weaknesses & bitterness as in Kurosawa's film, but temper a deeper humanity. Set largely in an alley on a set as grimy as in Kurosawa's The Lower Depths (Donzoku, 1957), the sorrows & tragedies reveal not weaknesses & bitterness as in Kurosawa's film, but temper a deeper humanity.

At this time, jidai-geki had been banned during the Occupation as promoting feudal values. Many a samurai film star went unemployed in the films of the 'forties. Some made ends meet by journeying to the hinterlands with small theater troupes.

But Bantsuma had proven himself capable in modern drama with the modern drama The Rickshaw Man; aka, The Life of Matsu the Untamed (Muhomatsu no Issho, Daiei 1943).

The Rickshaw Man is a moody tale of the poor rickshaw man Matsugoro (Bantsuma), he falls for a young widow (Keiko Sonoi, an actress who died in the bombing of Hiroshima) well above his station.

In her struggles she relies on him as one might a brother, but he dreams of more. He would love to become the actual father of her little boy (Hiroyuki Nagato), but has no hope of being anything but a friend to them. In her struggles she relies on him as one might a brother, but he dreams of more. He would love to become the actual father of her little boy (Hiroyuki Nagato), but has no hope of being anything but a friend to them.

A stunning film visually, & Bantsuma gave a tremendous performance that proved he was a lot more than an action star.

And so this "new" Batsuma of the sound era was equally suited to Osho. That someone reedy voice heard in his first talkie never left him, but the public got over the shock that he didn't have an exaggeratedly manly way of speech.

What he had instead was the ability to give even greater depth to performances. What he had instead was the ability to give even greater depth to performances.

He still had that incredible physical language he possessed in the silents, but now understood also how to use his voice, that of the common man with all that means of quiet heroism & sorrows.

And as the lower class shoji player mingling above his station for the sake of a game, he brings an amazing capacity to be both humble & presumptuous, devoted as he is to the full spirit of the game.

Nor is this a simplistic story of a game between a rich villain against a man of humble existence, as Sekine respects his challenger, does not judge him by his origins or his manners but only by his skill. It's really a thrilling drama.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

In the 1930s as sound was displacing the benshi live narrators of the silent film houses, the most popular actor of the silent era, Tsumasaburo "Bantsuma" Bando, was at risk of losing his audience.

In the 1930s as sound was displacing the benshi live narrators of the silent film houses, the most popular actor of the silent era, Tsumasaburo "Bantsuma" Bando, was at risk of losing his audience. Ito ended up with a silent film performance that might've worked better without spoken dialogue.

Ito ended up with a silent film performance that might've worked better without spoken dialogue.

Along an alley street next to the railroad, Koharu (Mitsuko Mito) struggles to make a home as the suffering wife of an endearing wastrel Sankichi Sakata (Bantsuma).

Along an alley street next to the railroad, Koharu (Mitsuko Mito) struggles to make a home as the suffering wife of an endearing wastrel Sankichi Sakata (Bantsuma). He is changed by the encounter. He decides to stop being a slacker & work hard for his family. But at the same time he wants to study shogi with ferocity, to become an undefeatable master.

He is changed by the encounter. He decides to stop being a slacker & work hard for his family. But at the same time he wants to study shogi with ferocity, to become an undefeatable master. Set largely in an alley on a set as grimy as in Kurosawa's

Set largely in an alley on a set as grimy as in Kurosawa's  In her struggles she relies on him as one might a brother, but he dreams of more. He would love to become the actual father of her little boy (Hiroyuki Nagato), but has no hope of being anything but a friend to them.

In her struggles she relies on him as one might a brother, but he dreams of more. He would love to become the actual father of her little boy (Hiroyuki Nagato), but has no hope of being anything but a friend to them. What he had instead was the ability to give even greater depth to performances.

What he had instead was the ability to give even greater depth to performances.