Part IV: Still More Race Stereotypes in Vintage Cartoons

The race stereotypes of African Americans in animated films most especially of the 1930s & 1940s were often intended, it has been claimed, as "adoring tributes" to black culture.

The race stereotypes of African Americans in animated films most especially of the 1930s & 1940s were often intended, it has been claimed, as "adoring tributes" to black culture.

The animators believed there was nothing racist about it, that they "celebrated rather than exploited black culture." Maybe very rarely there may have been something about a given cartoon to merit this self-agrandizing belief among the animators & more than a few of today's animation fans.

But for the majority of these films, the fact remains, the recurring use of lazy darkies with lower lips so big they could almost trip on them, pickaninnie children, white characters or animal-people in blackface, mammies in bandanas, & a general tendency to make these "celebrated" figures look more like monkeys than human beings, is an "adoring tribute" to nothing but the animators' own belittling & unthinking racism.

And that's before we even get to Africa itself, consistently portrayed as populated by ape-like half-humans with bones in their hair or through their noses, chasing white people with spears, & having big black iron cauldrons in which to cook white people.

Spear-chuckers & jazz sambos were never African American culture. The lack of African American input from the creative end of the cartoon industry guaranteed honkeys would have no clue as to whose culture they reflected, as this insulting sewage comes right out of white America's worst attitudes about blacks even if pretending to like that which they don't know nothing.

The diehard claims to the contrary confuses cultural racism with personally being racists. I'm sure few if any of the cartoonists were out & out racists. But racism is cultural, & the racism was pervasive, resulting in nearly exclusive use of demeaning stereotypes as shortcuts to alleged humor.

This is not to justify censorship. It makes sense not to show such cartoons morning or afternoon when unformed minds of children can be imprinted with derogatory stereotypes we don't need passing through the generations, showing them latenight only, or via dvd.

But in some cases, cartoons withdrawn from circulation in the 1960s at the height of Civil Rights sensitivity are still withheld from circulation by the copyright holders & are difficult to obtain through legitimate sources in remastered or restored condition. These films are historically important & in a few cases are even great art in their own right. Keeping them hidden away is as offensive as the most racist of the cartoons.

It's my intent to consider the content of some of these troubling works, striving to sort out the artful from the tawdry, separate the rare moments when "adoring tribute" might almost apply, & assess the racist content of the majority; & ultimately to identify which are fine works of animation even with problematical content. It's not an easy chore to balance the purely aesthetic with the socially aware, as much hinges upon personal opinion & personal experience.

Opening with the title song Hittin' the Trail for Hallelujah Land (1931), we see a steamboat heading down the Mississippi, but the song itself sounds rather like western swing. It's being performed by three black guys on deck of the boat, one with banjo, one with harmonica, one with clacking bones. Opening with the title song Hittin' the Trail for Hallelujah Land (1931), we see a steamboat heading down the Mississippi, but the song itself sounds rather like western swing. It's being performed by three black guys on deck of the boat, one with banjo, one with harmonica, one with clacking bones.

They're pleasant singers & as black caricatures go they're not the worst by any means & they're not doing anything that would offend. Will it get worse to justify this being one of the infamous "banned eleven" race cartoons? Let's find out.

The all-black cast or at least blackface cast of animals includes pig-people (boy Piggy & girl Fluffy, who are sweethearts), duck-people, dog-people (including an old man called Uncle Tom & patterned after the original Uncle Tom's image), & others.

They're pretty regular cartoon figures really whose blackness in this rare case is not exaggerated. Some of the characters in any other cartoon might not even be noticed to be black, unless Mickey Mouse is a negro (which, hey, isn't out of the question). They're pretty regular cartoon figures really whose blackness in this rare case is not exaggerated. Some of the characters in any other cartoon might not even be noticed to be black, unless Mickey Mouse is a negro (which, hey, isn't out of the question).

As a very early talking film made in black & white by Warner Brothers in conjunction with Vitaphone, Hittin' the Trail for Hallellujah Land has considerable historical importance. It is inspired to some degree by the first all-black all-sound musical Hallelujah (1929) though there are no real parodic moments alluding to that film's content.

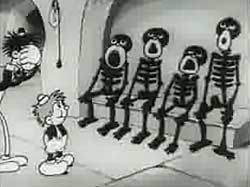

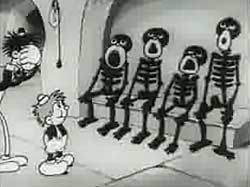

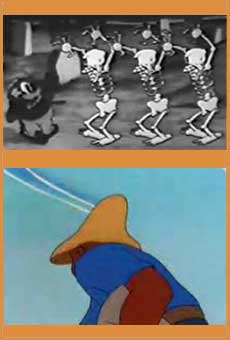

Uncle Tom falls off his mule-drawn wagon & lands over a fence in the graveyard. "Holy mackerel!" he says, parroting Amos & Andy which had started on the radio in 1928. He is frightened to meet a harmony group of skeletons with whom he sings in a terrified manner. The scene is derivative of Disney's The Skeleton Dance (1929), just as scenes with Piggy as riverboat captain are derivative of Steamboat Willy (1928).

Tom running from skeletons is the sort of surrealism seen in scores of cartoons of the time & nothing about Tom being black really plays into the old stereotype of blacks more than whites being scared of ghosts. It's merely a standard gag & the character could just as easily have been Betty Boop. Tom running from skeletons is the sort of surrealism seen in scores of cartoons of the time & nothing about Tom being black really plays into the old stereotype of blacks more than whites being scared of ghosts. It's merely a standard gag & the character could just as easily have been Betty Boop.

So I'm still waiting for scenes that would justify it being withheld from distribution by United Artists in 1968 & still today withheld by Warner Broadcasting. So far, I'd be willing to book it into a black theater to play along with an Oscar Mischeaux film made by & for the African American community.

It ends with Fluffy needing rescue from a typical mustachioed villain from stage melodramas & vaudeville, & a romantic reuinion with Piggy. This cartoon is crammed with imaginative moments, & I gotta say, this was banned because the characters were black, not because they were offensive, a case of tossing out the baby with the bathwater.

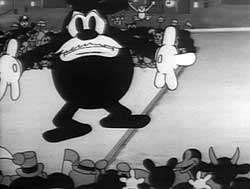

Piggy & Fluffy were intended as series characters but they appear in only two cartoons. The earlier one was You Don't Know What You're Doing (1931), with music by Gus Arnheim's orchestra. Fluffy & Piggy go to a concert, at which Piggy ends up in a musical duel with the band's lion conductor, Piggy on sax against the trumbone player caricaturing Gus.

In this one it is not at all intended that the characters are black, though no alteration of their design was necessary to make them so in their second & final film. In this one it is not at all intended that the characters are black, though no alteration of their design was necessary to make them so in their second & final film.

It's not inconceivable they were intended as black from the start, as with the early b/w Bosko cartoons, & Piggy does rather resemble the original Bosko (not the revamped technicolor Bosko who is a regular black kid).

There is a race-stereotype moment in the film, though, when Piggy's animate motorcycle "farts" smoke in an usher's face turning him black & inducing him to say, "Mammy!" Sound films of such early vintage were apt to make this "Mammy" reference from Jolsen's The Jazz Singer (1927) as Jolsen's song provided a wildly important moment for early sound, which would be referenced in many a cartoon for the next couple decades.

The two Piggy & Fluffy cartoons were created in response to Walt Disney asking Rudolph Ising to stop making Merrie Melodies with the character of Foxy who looked almost exactly like Mickey.

Rudy was willing to comply but already had two more Foxy cartoons in the works, so came up with a cartoon character design that would fit in the spots prepared for Foxy & his girlfriend. This begs the question of whether or not Foxy & his girlfriend were also negro! They certainly aren't white.

Another group of skeleton singers turn up as a black harmony group in Van Beuren Studio's first cartoon featuring Tom & Jerry, the tall & short gents, not the cat & mouse who came later with the same names.

Another group of skeleton singers turn up as a black harmony group in Van Beuren Studio's first cartoon featuring Tom & Jerry, the tall & short gents, not the cat & mouse who came later with the same names.

In Wot a Night (1931), Tom & Jerry are at the train depot waiting in their Taxi cab hoping to get a fare. There's a terrible storm that even makes the cab sneeze. "Here it comes!" says Jerry & the train rolls right through the flood & stops at the platform.

They get skinny twins in top hats as their fares, & drive them through the deluge to a walled castle, following them inside because they failed to pay.

A storm cloud begins to play the castle's crenels as organ keyes, & the castle towers are pipes of a pipe organ. Leafless trees in the storm play their own limbs as flutes.

A bat-vulture-ghost appears to Tom & Jerry but then just flies away. They next encounter a skeleton taking a bath, whistling all the while he's drying himself off. Lots of ghosts appear behind Tom & Jerry, followed by numerous ghostly manifestations, few with any gags attached.

A skeleton-pianist's playing brings a number of piles of bones to life for some dancing. Some of these bone-men are coal-black skeletons who sing about wantin' to get to "hebbin." Jerry likes it; Tom seems scared.

It's a nice, rather primitively animated cartoon with a creepy ending, in which Tom & Jerry realize they're skeletons too. As for the jubilee harmony skeletons, there are some who would find it offending, but I think that would be oversensitive indeed, & should wait for the Tom & Jerry episode

Plane Dumb (1932) to get up in arms about these guys.

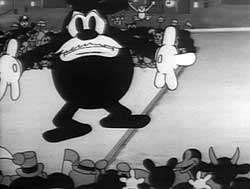

Any Bonds Today? (1942) titled for the Irving Berlin song was "Produced in cooperation with Warner Bros. & U.S. Treasure Dept. Defense Savings State."

Any Bonds Today? (1942) titled for the Irving Berlin song was "Produced in cooperation with Warner Bros. & U.S. Treasure Dept. Defense Savings State."

In promoting war bonds, this minute & a half cartoon decided to include a blackface routine, which in 2001 got it added to the Times Warner list of a dozen Bugs Bunny cartoons banned from television.

Bugs give a rhyming rap, song, & dance version of the title song, pitching right to the audience to buy bonds. Suddenly Bugs is in blackface & does an Al Jolsen routine incorporating bits of "Mammy." This lasts a few seconds then Porky & Elmer Fudd come out in uniforms to dance out the the show.

Censorship is wrong but I can agree with not showing cartoons with offensive stereotypes to children. This one seems not at all agregious & I wouldn't've put it on the not-for-kids list. The real trouble comes when Warner bans something & because they control the rights, it becomes increasingly hard for adult animation fans to obtain.

Living in a beautiful cabin-like treehouse birdnest in the rural south are three baby blackbirds & their mammy (with bandana).

Living in a beautiful cabin-like treehouse birdnest in the rural south are three baby blackbirds & their mammy (with bandana).

These blackbirds of The Early Worm Gets the Bird (1940) are pretty regular cartoon characters not given stereotypical traits other than dialect speech, & for once we have an old classic that was never banned for its blackness, proving it could be tastefully done.

Mammy is stereotypical of the Aunt Jemima type, but if that was the worst stereotypes ever got, they wouldn't cause a fuss. She tells young William & his siblings about the horrible monstrous fox, warning them that if they go off hunting worms alone, the fox will get them sure.

But William says, "I ain't afraid of no fox," & sets his clock early so he can get up & go hunt worms.

At cock's crow William tiptoes out of the cabin-nest & glides down to the ground, worm-huntin'. A baby caterpillar has heard the same story about the early bird getting the worm, & sets out in curiosity to see what a bird looks like.

Upon encountering one another, each is afraid of the other, but soon they're in a battle of wits which the worm seems liable to win. The worm is a black kid, too. But other than slight phony dialects like when William says "Where is you! Come out & fight like a worm!" there is very little stereotyping going on & it's a largely positive portrait.

Before long the red fox shows up just like Mammy warned. William doesn't know what a fox looks like, though, & at first innocently befriends the wiley critter as though both of them are after the worm.

Soon he's on sandwich bread but before the fox can eat him, the worm saves William's life, & the two kids, bird & worm, are fast friends forever. This is a great cartoon & quite a surprise in presenting an essentially black cast with dignity.

Pretty much the same characters of William & his mammy appear not as blackbirds but as hen & chick in Flop Goes the Weasel (1943).

A Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies film Mississippi Hare (1949) opens with a rendition of "I Wish I Were in Dixie" as the camera pans into a cottonfield with black folks picking cotton, focusing at last on a single worker. This is a Romanticist portrait, the worker looking like a powerful fellow plucking cottonballs, accidentally picking up Bugs Bunny by his cotton-tail & putting Bugs in a sack with cottonballs.

A Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies film Mississippi Hare (1949) opens with a rendition of "I Wish I Were in Dixie" as the camera pans into a cottonfield with black folks picking cotton, focusing at last on a single worker. This is a Romanticist portrait, the worker looking like a powerful fellow plucking cottonballs, accidentally picking up Bugs Bunny by his cotton-tail & putting Bugs in a sack with cottonballs.

Bugs then gets processed into a cotton bail & is loaded onto a riverboat to be shipped north. Escaping from the bail, he soon disguises himself as a wealthy traveller & begins to interact with workers & passengers on the riverboat.

A two-gun gambler is a varient of Yosemite Sam. The Colonel is the "rip-roarin'est, gol dingin'est, sharp shootin'ist, poker-playin'ist riverboat gambler on the Mississippi. Is there anyone man enough to sit in a poker game with Colonel Shuffle? Well? Be there?"

Bugs says, "There be," & sits down to take the colonel for all he's worth, resulting in the soar loser seeking a duel with pistols. Bugs gives the colonel an exploding cigar, resulting in the time-honored offensive blackface gag. Having one's face blackened by such a cigar results in the instant ability to play "Camp Town Races" on the banjo while looking cross-eyed & stupid.

For conclusion Bugs also does a drag routine as a southern belle beating the crap out of the colonel, then seduces a chivalrous gentleman to fight the colonel for "her." Bugs seemed really willing to have a gay fling with the gentleman.

For a film set in the Deep South, Mississippi Hare managed not to be too awfully spiteful about African Americans, in the main by ignoring their existence in the South. The cottonpicker at the beginning was a largely inoffensive stereotype, &;amp the seriously unnecessary blackface gag was more unimaginative than racist.

And yet the film did end up censored because it dared to show a black man picking cotton & included the lame blackface gag. The scene of the colonel in blackface & the opening with the cottonpicker was removed for showing on ABC & the no longer extant WB channel. The Cartoon Network in 2001 put this one on a list of twelve Bugs cartoons not to be shown at all due to assumed offensiveness to African Americans.

It's idiotic decisions like that which make angry little putzes whine like a pack of KKK wannabes about "the politically correct police." A typical world wide web commentator said that depriving him of his blackface & cottonpicker scene "sounds like modern-day Nazism."

He didn't notice the gun-fired-directly-in-face sequence was also censored from the CBS & WB showings as too much an instructional to small children on how to handle guns. It only bothered him to miss out on one or two moments of milder racism, which deprivation he believes comparable to killing millions of Jews & Gypsies.

The derogatory term "politically correct" was initially popularized by right-wingers to condemn even the simplest human decency as crimes of liberal academics, minorities, & women.

So even if an act of censorship is performed by cowardly overreacting executives of a major corporation who care nothing about the cartoons they feature (& this executive population is not overburdened with academic, minority, or female members) it is automatically the fault of those damned lefties, i.e., the "politically correct" brigade, straw dogs for little minds that can't think up any intelligent reasons for struggling against censorship, a struggle which tends to be much more greatly the province of those fearful lefties.

Worried more about advertising dollars than who is offended, the executives with no interest in guidelines to recognize actual racism consider it safe passage to excise anything that might offend parents or minorities & thereby advertisers.

Thus cartoons will have removed from them innocuous stereotypes along with agregiously offensive ones, as well as any jokes about suicide (excised by ABC & Nickelodeon from Martian Through Georgia, 1962), weapons violence (excised by TNT from Mexican Joyride, 1947; excised by ABC from Mouse-Taken Identity, 1957; & a huge number of such examples), drunkenness (excised by ABC from A Mouse Divided, 1953, & from Apes of Wrath, 1959), or smoking (excised by ABC from My Little Duckaroo, 1954 & by CBS from Beanstalk Bunny, 1955). For a while, ABC was excising scenes wherein cartoon characters catch fire.

For shows aired early in the day for children, some of these edits probably shouldn't be deplored or faulted too much, just so long as the complete version is still available on dvd to serious collectors who value animation as a legitimate American artform. Better would be schedule questionable cartoons for late-night only & not expose children to them. It's more unfortunate when such films are completely withdrawn from circulation, or end up even on dvd compilations in truncated versions.

For scores of examples of all kinds of censorship, not just for racism, see the extensive Censored Cartoons Pages.

Continue to Part V:

Race Stereotypes & Censorship in Classic Animation

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

They're pretty regular cartoon figures really whose blackness in this rare case is not exaggerated. Some of the characters in any other cartoon might not even be noticed to be black, unless Mickey Mouse is a negro (which, hey, isn't out of the question).

They're pretty regular cartoon figures really whose blackness in this rare case is not exaggerated. Some of the characters in any other cartoon might not even be noticed to be black, unless Mickey Mouse is a negro (which, hey, isn't out of the question). Tom running from skeletons is the sort of surrealism seen in scores of cartoons of the time & nothing about Tom being black really plays into the old stereotype of blacks more than whites being scared of ghosts. It's merely a standard gag & the character could just as easily have been Betty Boop.

Tom running from skeletons is the sort of surrealism seen in scores of cartoons of the time & nothing about Tom being black really plays into the old stereotype of blacks more than whites being scared of ghosts. It's merely a standard gag & the character could just as easily have been Betty Boop. In this one it is not at all intended that the characters are black, though no alteration of their design was necessary to make them so in their second & final film.

In this one it is not at all intended that the characters are black, though no alteration of their design was necessary to make them so in their second & final film.