Medieval Yakuza Part I:

Kunisada Chuji & His Historical Relevance

Viewed through Early Cinema

The common people were not as subservient to Japan's feudal system as often supposed. Rebellion was endemic throughout Japanese history, even in the "peaceful" Tokugawa era. The common people were not as subservient to Japan's feudal system as often supposed. Rebellion was endemic throughout Japanese history, even in the "peaceful" Tokugawa era.

Whenever peasants were pushed too far, there were peasant uprisings when the buke samurai class became too overbearing & discovered that farmers with orchard saws or winnowing flails could use their implements as weapons. So too there were "rice riots" protesting hunger & taxation.

The rebelliousness of commoners when tyranny overstepped itself meant there were periods of genuine peace only because regional lords or daimyo were afraid of the possibility of chaos if peasants were displeased.

Numerous individuals & groups undermined the status quo. Commoners formed groups of kyokaku ("heroic host" or "town knights") later also called ototodate ("daring fellows"). They were obedient to bosses who were like fathers of a family. These gangs lived under a code of conduct called kikotsu, equivalent to the samurai's bushido code. This code encouraged rebellious outrage in the face of injustice.

A typical "kyokaku" town knight is shown in the 1849 block print by Ittosai Masanobu, depicting the actor Kataoka Gado II as Honchomaru Tsunagoro, from a set of such prints called Date kurabe kyokaku-den, or Stylish and Well Known Gallants. As kyokaku were never of the samurai class, they carried one sword rather than two, but frequently, as a means to show off, the sword would be unusually long, longer than those of samurai. Swords are shown as such in almost all late Tokugawa & early Meiji kyokaku portraits.

The second Edo period kyokaku portrait is an illustration for a book in the Noda Public Library rare books collection. Again he has the long sword, even though he's indoors & should've put it aside except for vanity's sake. The second Edo period kyokaku portrait is an illustration for a book in the Noda Public Library rare books collection. Again he has the long sword, even though he's indoors & should've put it aside except for vanity's sake.

Though Chuji of Kunisada Village in Joshu (today, Gunma Prefecture) was a legendary outlaw hero, he was most certainly of an actual historic type. Some say he was a real man whose real name was Chujiro Nagaoka, a farmer born in Joshu in 1810.

This Chujiro Nagaoka became an outlaw who did some roundly bad things, but managed even so to gain a reputation for a few good things as well. When the government decided to clear the highways of bandits, this fellow, who may have been the original Chuji, essentially vanished for some years from the face of history, probably living a quiet & ordinary life. But in 1850 he was arrested & executed. This, of course, is not the preferred story of Chuji's life & deeds.

A rough outline of his legend has it that in 1846 he established a great gambling hall & became a powerful oyabun or gambling boss. He had one wish in life: "I want to die in a manner that all the people will mourn me." When government officials harrassed the commoners who looked up to him, he would intercede, nonviolently at first. Eventually he came to blows with the authorities & had to flee to a mountain retreat, from which location he remained as a threat to tyranny.

His legend has been fleshed out into a rich biography in folk tales, folk songs, literary fictions, plays, motion pictures, television programs, comic books, anime, & video games. A few seconds of a Chuji folkplay can be glimpsed in Kaneto Shindo's Life of Chikuzan the Shamisan Player; aka, Chikazu's Lone Journey (Chikuzan hitori tabi, 1977). His legend has been fleshed out into a rich biography in folk tales, folk songs, literary fictions, plays, motion pictures, television programs, comic books, anime, & video games. A few seconds of a Chuji folkplay can be glimpsed in Kaneto Shindo's Life of Chikuzan the Shamisan Player; aka, Chikazu's Lone Journey (Chikuzan hitori tabi, 1977).

This film starred Ryuzo Hayashi as Chikuzan Takahashi, a modern-day blind wanderer who collected folksongs all around Japan & in his later years (in the 1960s & 1970s) became a recognized national treasure. He lived an actual life patterned to some degree after the likes of Chuji Kunisada, not where crime was concerned, but in terms of the perpetual journey.

Kaneto Shindo, a left-leaning director, intentionally wished to draw a comparison between Chuji the chivalrous commoner of legend & this modern folksinger.

The image reproduced here from the video box shows the central figure playing shakuhachi rather than shamisen, & shows him wearing the sedgehat of a matatabi or wanderer exactly as would've been worn by Chuji & his men when on the road.

Chuji with his men on Mount Akagi are as familiar to every Japanese as Robin Hood & his men of Sherwood Forest are to English-speaking westerners.

Daisuke Ito's A Diary of Chuji's Travels (Chuji tabinikki I, II, 1927; III, Nikkatsu, 1928) features Denjiro Okochi as the legended gambler of the late Edo period. Daisuke Ito's A Diary of Chuji's Travels (Chuji tabinikki I, II, 1927; III, Nikkatsu, 1928) features Denjiro Okochi as the legended gambler of the late Edo period.

According to film historian Donald Richie, Chuji is portrayed in this silent epic as a veritable revolutionary at odds with an oppressive system.

The epic originally stretched to four hours, of which 94 minutes survive in a rough restoration, nearly the entirety of part II & half of part III, giving the whole of the story about the geisha Oshina (Naoe Fushimi) whom Chuji strives to save, followed by a story of Chuji's loss of reputation & final downfall.

Three stills from Ito's epic of Chuji Kunisada are shown near these paragraphs. A fourth still is at the top of the page, together with an advertisement image for Ito's film & a 19th Century portrait of Chuji. Three stills from Ito's epic of Chuji Kunisada are shown near these paragraphs. A fourth still is at the top of the page, together with an advertisement image for Ito's film & a 19th Century portrait of Chuji.

Ito's period films in general promoted nearly socialist ideals, as he was noted for Keiko Eiga or "films leaning left." The idea of a hero like Chuji from outside the ruling military class lends himself to social commentary even in a film of action & entertainment.

Today the name kyokaku is used as a euphemism for the modern, criminal yakuza, gangsters who retain the same boss-gang relationships as the feudal yakuza, but not the ideals attributed to the likes of Chuji.

Truth be told, the original kyokaku were not all that idealistic either, as there can be a considerable distance between a code & its implementation. But there are entirely historical examples of men exactly as noble as Chuji. Truth be told, the original kyokaku were not all that idealistic either, as there can be a considerable distance between a code & its implementation. But there are entirely historical examples of men exactly as noble as Chuji.

Many of the nobler attributes of kyokaku were expressed not in the Tokugawa era when such gangs flourished, but later on, in the Meiji period at the turn of the 19th Century, when the equivalent of dime-novels (called matatabi-mono) were first widely circulated. These heroized the kyokaku -- much as did America's penny dreadfuls glamorize Billy the Kid or Jesse James.

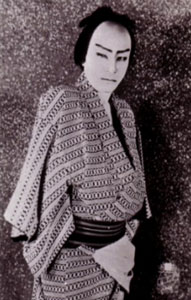

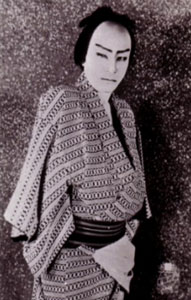

A year before Daisuke Ito's famous version, Tsumasaburo Bando starred in a ten-reel epic Kunisada Chuji ochiyuku oshuji (Bantsuma Production, 1926), produced by his own company.

A year before Daisuke Ito's famous version, Tsumasaburo Bando starred in a ten-reel epic Kunisada Chuji ochiyuku oshuji (Bantsuma Production, 1926), produced by his own company.

This film alas does not survive, though we can guess it was a grand version judging by the startlingly realistic swordplay & storytelling values the star achieved in his films of this period which do survive.

A still of Tsumasaburo in character for this film is shown near this paragraph, as the only taste of the film we can today acquire.

The kyokaku & otokodate were also known as yakko, a word which implies servitude to the gang boss. It may also be the root word for "yakuza," but the entymology is clouded. A classic example of the Japanese pun, the individual syllables of the word "yakuza" correspond to certain numbers on a gambler's dice, but taken together mean literally "useless person," a typical self-deprecation.

In theory these "useless persons" were supposed to hide in the shadows, avoiding the law, & never pestering "honest" people. In theory these "useless persons" were supposed to hide in the shadows, avoiding the law, & never pestering "honest" people.

Gambling & even prostitution were illegal but they were services sought out by many people; if no one sought out yakuza for the sake of these services, then moral individuals should in accordance with the gangster code never be molested by yakuza.

In reality of course, yakuza could be as troublesome to honest people as were the overbearing samurai, & only a chivalrous yakuza would endorse & obey the gamblers' code, & enforce the code when the more typical gangsters behaved wrongly.

In the first Zatoich film, Life & Opinions of Masseur Ichi (Zatoichi monogatari, 1963), Ichi chastises a group of his fellow yakuza about how wrong it has been of them to live in the sunlight & bother good people. Then he corrects the trouble by killing everyone he disapproves of.

Zatoichi's character, except for being blind, was to great extent patterned after Chuji Kunisada, as Ichi follows the same code Chuji honors, keeping to the shadows & assisting persecuted peasants. In Zatoichi the Fugitive (Zatoichi kyojo-tabi, (1963) & in Zatoichi & the Chest of Gold (Zatoichi sen-ryo kubi, 1964), Chuji & Ichi actually join forces, & Chuji's advice to Ichi is typical of his famous wit: "We may not live long. Let's shake the world while we can!"

Early in the Tokugawa period, the kyokaku organizations were useful in lessening the power of oppressive government. An otokadate boss named Chobei of Banzui became a noted power in the capital, Edo. He was a chonin or "townsman" & used his power to aid artisans & merchants inside the city.

Early in the Tokugawa period, the kyokaku organizations were useful in lessening the power of oppressive government. An otokadate boss named Chobei of Banzui became a noted power in the capital, Edo. He was a chonin or "townsman" & used his power to aid artisans & merchants inside the city.

The attached ukiyo woodblock print by Kuniyoshi shows Banzui Chobei as a representative "manly type." His type was thoroughly historical even if everything that is known about Chobei is legendary in nature, making him a standard figure for kabuki plays, most famously in Kawatake Mokuami's Kiwametsuki Banzui Chobei (1881).

From Chobei's more-or-less historical reality we can see the origins of Chuji. The sort of power Chobei wielded in favor of the people was a nuisance to the shogunate. Eventually these yakuza prototypes were expelled from Edo, after many terrible riots & encounters bertween samurai & otokodate.

Once expelled from Edo, these gangs set up de facto rule in post towns. They were never completely suppressed because they began to make concessions to the shogunate through easily corrupted local officials. To finance their activities they organized illegal gambling & lower-class brothels. Sometimes they were literally funded to get started in their criminal enterprises by the shogunate itself, which got kickbacks from the businesses. The government could thus hire laborers at sightly inflated wages with every expectation of getting a percentage of the payroll back when laborers squandered their earnings gambling & whoring.

This very likely marked the end of the kyokaku & otokodate as an element of rebellion, much as the mafia of Sicily has its root in peasant defense but over time became increasingly a criminal organization. The medieval yakuza were coopted as part of the system, & to this day yakuza organizations can be found with clearly marked offices, or looked up in the phone book, as they are regarded as a necessary evil keeping young men who might otherwise be thugs in check by their obedience to their oyabun/godfather.

This background helps in understanding why, in so many of the Zatoichi films, Ichi arrives in a village terrorized by gangsters who are immune to any official authority of the Tokugawa government, & demanding Ichi's vigilantism to restore a certain balance of fairness. This is also the world exposed by Chuji, who is against bad gangsters as much as he is against tyrannical government officials. Frequently in Zatoichi's universe, there is a "good" yakuza gang like that of Chuji's, but a "bad" gang is in the pocket of some shogunate official.

Inevitably these post town gangs instigated Tong Chinatown or Chicago-gangland type levies on merchants, purportedly to protect them from overbearing samurai but really to keep the gangs themselves from causing trouble. In cinematic treatments, town officials of the samurai class who had turned a blind eye to the goings-on in trade for their kickbacks are apt to be killed right alongside the gangsters.

The legend becomes, thereby, not that the kikotsu code made the medieval yakuza worthy decent heroic types, but that once in a great while someone like Chuji or Zatoichi would take the kikotsu code extremely seriously, & their chivalrous personalities were awakened by others' refusal to honor any code but their own thirst for money or power.

So yakuza like the Tong of China or the Sicilian mafia originated in self-protection leagues that quickly began to misuse their power for self-perpetuation & monetary gain, losing their original intent to defend the defenseless. Yet always the original kikotsu system of ethical behavior lingered in the background as a chastisement against the unfortunate behavior of gangsters, providing an excuse for the chivalrous gambler to intercede on behalf of humane sentiment.

Hence the legends of superhero gambling warriors arose. The exploits of such gamblers became meat of popular literature & folktales & classical theater &, by the earliest days of cinema, movies.

Daisuke Ito's Chuji trilogy was followed by Inagaki's 1933 Chuji trilogy starring Chiezo Kataoka.

Daisuke Ito's Chuji trilogy was followed by Inagaki's 1933 Chuji trilogy starring Chiezo Kataoka.

These were Kunisada Chuji: Tabi no kyoko no maki (Chuji Kunisada 1: Travel & Home, Chie, 1933); Kunisada Chuji: Ruru ruten no maki (Chuji Kunisada 2: Wandering & Change, Chie, 1933); & Kunisada Chuji: Hareru Akagi no maki (Chuji Kunisada 3: Clear Skies Over Akagi, Chie, 1933).

Each of these three films was a nine-reel full-length feature, but are evidently irrecoverably lost films. The still reproduced with this section gives a flavor of what we unfortunately no longer possess.

However, Inagaki's very first silent film Horo Zanmai (Wandering Gambler; aka, Wanderlust, Nikkatsu, 1928) with a similar character, & the same star, is preserved by the Japan Film Library Council in Tokyo. However, Inagaki's very first silent film Horo Zanmai (Wandering Gambler; aka, Wanderlust, Nikkatsu, 1928) with a similar character, & the same star, is preserved by the Japan Film Library Council in Tokyo.

A slim contemporary poster for Horo Zanmai is shown near this paragraph, as also the box design for the film as available from the Matsuda silent film institute.

Horo Zanmai was a silent hour given voice by a benshi's narration, telling a story set at the tail-end of the Tokugawa era. Mondo (Chiezo Kataoka) sets out on the road of revenge after he finds his wife Tsuyu (Junko Kinugasa) dead, having killed herself due to being blackmailed over an intemperate letter.

The story has him achieving vengeance against his late wife's persecutor, then Mondo heads out on the lam with his young son Kotaro as eternal wanderers. The story has him achieving vengeance against his late wife's persecutor, then Mondo heads out on the lam with his young son Kotaro as eternal wanderers.

It can't be coincidence that Kotaro's name sounds a lot like Kantaro, an orphan character associated with Chuji.

Multiple storylines render that simple story more convoluted than necessary. Chiezo draws on his kabuki training, toned down for realism's sake but still a bit over the top compared to his later completely realistic performances.

His training for the stage allowed him come up with some of the most amazing physical stances & facial expressions during scenes rapid swordplay action.

Another version of Kunisada Chuji (Chuji of Kunisada, Tao Tojin, 1924 or 25) was directed by Shozo Makino, preserved in the Kyoto Film Library. Another version of Kunisada Chuji (Chuji of Kunisada, Tao Tojin, 1924 or 25) was directed by Shozo Makino, preserved in the Kyoto Film Library.

A still from this version is reproduced by this paragraph, showing Chuji seated on a roadside between two companions.

This is one of the more important Japanese silents to have survived. It stars Shojiro Sawada, himself an actor of both screen & kabuki stage who had first performed the role on stage in 1917, for the highly influential New National Theater which he himself founded. It was described by film essayist Sadao Sato as having "lively, realistic swordfights & a quasi-revolutionary hero," so from early on Chuji's cinematic presentation he had a left-leaning political edge.

Other of Shozo's silent films about Chuji do not survive. These were Kunisada Chuji (Chuji of Kunisada, Kokatsu, 1922) starring Hataya Ichikawa; & Kunisada Chuji: Nikko enzo to Kunisada Chuji (Chuji Kunisada: Enzo of Nikki & Chuji of Kunisada, Nikkatsu Tokyo, 1914), starring kabuki-style actor Matsunosuke Onoe.

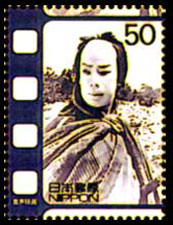

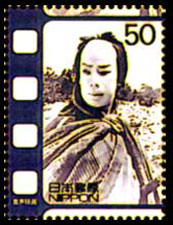

Onoe played in additional films titled Kunisada Chuji in 1918, 1921, & 1925, though apparently none of these have survived. A 1999 commemorative postage stamp, however, features a still of Onoe in this role, though which film it might've been for is not known (the stamp is shown here). Onoe played in additional films titled Kunisada Chuji in 1918, 1921, & 1925, though apparently none of these have survived. A 1999 commemorative postage stamp, however, features a still of Onoe in this role, though which film it might've been for is not known (the stamp is shown here).

Shozo Makino's son was a leading jidai-geki director of the following generation, & his Chuji film A Man's Pledge is reviewed in detail in Part II of this essay.

Chuji films became a veritable sub-genre of the matatabi-mono or traveller tales category of jidai-geki (period swordplay films). They'd be important when the sound era arrived, they'd still be important after the Occupation, & new versions are still being filmed to this very day. The next sections of this lengthy overview will look at high points of these treasures of cinema.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

The second Edo period kyokaku portrait is an illustration for a book in the Noda Public Library rare books collection. Again he has the long sword, even though he's indoors & should've put it aside except for vanity's sake.

The second Edo period kyokaku portrait is an illustration for a book in the Noda Public Library rare books collection. Again he has the long sword, even though he's indoors & should've put it aside except for vanity's sake. His legend has been fleshed out into a rich biography in folk tales, folk songs, literary fictions, plays, motion pictures, television programs, comic books, anime, & video games. A few seconds of a Chuji folkplay can be glimpsed in Kaneto Shindo's Life of Chikuzan the Shamisan Player; aka, Chikazu's Lone Journey (Chikuzan hitori tabi, 1977).

His legend has been fleshed out into a rich biography in folk tales, folk songs, literary fictions, plays, motion pictures, television programs, comic books, anime, & video games. A few seconds of a Chuji folkplay can be glimpsed in Kaneto Shindo's Life of Chikuzan the Shamisan Player; aka, Chikazu's Lone Journey (Chikuzan hitori tabi, 1977).

Three stills from Ito's epic of Chuji Kunisada are shown near these paragraphs. A fourth still is at the top of the page, together with an advertisement image for Ito's film & a 19th Century portrait of Chuji.

Three stills from Ito's epic of Chuji Kunisada are shown near these paragraphs. A fourth still is at the top of the page, together with an advertisement image for Ito's film & a 19th Century portrait of Chuji. Truth be told, the original kyokaku were not all that idealistic either, as there can be a considerable distance between a code & its implementation. But there are entirely historical examples of men exactly as noble as Chuji.

Truth be told, the original kyokaku were not all that idealistic either, as there can be a considerable distance between a code & its implementation. But there are entirely historical examples of men exactly as noble as Chuji.

In theory these "useless persons" were supposed to hide in the shadows, avoiding the law, & never pestering "honest" people.

In theory these "useless persons" were supposed to hide in the shadows, avoiding the law, & never pestering "honest" people.

However, Inagaki's very first silent film Horo Zanmai (Wandering Gambler; aka, Wanderlust, Nikkatsu, 1928) with a similar character, & the same star, is preserved by the Japan Film Library Council in Tokyo.

However, Inagaki's very first silent film Horo Zanmai (Wandering Gambler; aka, Wanderlust, Nikkatsu, 1928) with a similar character, & the same star, is preserved by the Japan Film Library Council in Tokyo. The story has him achieving vengeance against his late wife's persecutor, then Mondo heads out on the lam with his young son Kotaro as eternal wanderers.

The story has him achieving vengeance against his late wife's persecutor, then Mondo heads out on the lam with his young son Kotaro as eternal wanderers.

Onoe played in additional films titled Kunisada Chuji in 1918, 1921, & 1925, though apparently none of these have survived. A 1999 commemorative postage stamp, however, features a still of Onoe in this role, though which film it might've been for is not known (the stamp is shown here).

Onoe played in additional films titled Kunisada Chuji in 1918, 1921, & 1925, though apparently none of these have survived. A 1999 commemorative postage stamp, however, features a still of Onoe in this role, though which film it might've been for is not known (the stamp is shown here).