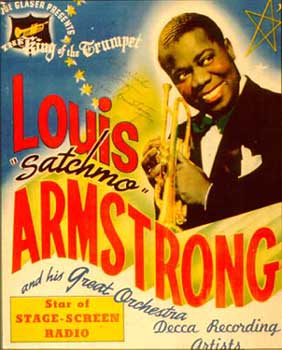

Louis Armstrong & His Orchestra are featured in the three-minute soundie Swingin' on Nothin' (1942), with Louis on his trumpet mugging & playing most pleasingly. He doesn't sing however; the singers are Velma Middleton & George Washington (usually Satch's trombonist), & they're absolutely great in a call & Velma's response: Louis Armstrong & His Orchestra are featured in the three-minute soundie Swingin' on Nothin' (1942), with Louis on his trumpet mugging & playing most pleasingly. He doesn't sing however; the singers are Velma Middleton & George Washington (usually Satch's trombonist), & they're absolutely great in a call & Velma's response:

"Swingin' all day (Swingin' on nothin')/ Swingin' away (Swingin' on nothin')/ Swingin' I say (Swingin' on nothin')/ Lord, lord." It's a delightful jump-jazz number. Velma throws in some scat. Throughout, Louis is a subdued presence conducting in the background, letting his vocalists have their day.

Velma & George even do a little dance together, & Velma's awfully light on her feet for a big gal, eventually spinning around on the floor as a breakdancer, including the full splits!

Velma was one of the great vocal talents of her era, & just about every working orchestra would have a female vocalist with them on the road for at least a few songs. Velma was one of the great vocal talents of her era, & just about every working orchestra would have a female vocalist with them on the road for at least a few songs.

But truth be told, Louis kept her on tour with him through much of the '40s not only because it met the expectation that he'd have a girl singer, but also because Velma was all that & a novelty act in the bargain.

If not for the hefty-gal breakdancing, Satch would very likely have stuck with himself & a couple bandmembers like George for the vocals. Because of her dancing, this soundie becomes much more a Velma Middleton vehicle than Louis'.

Big Sid Catlett gets a couple of close-ups on drums. This is a truly dynamite three minutes of entertainment, & one of the authentically classic soundies.

Sachmo's soundies were made as much for promotional purposes as for the visual jukeboxes so a little more went into them than the straightforward filming of the performance.

That can be good or bad depending on the film, & really it'd be enough to just watch Louis do his stuff. But there's enough wholly serious film footage of his performances around, it's fun to see the occasional piece of tomfoolery.

For Shine (1942) the stage is set with a gigantic shoe on a pedestal. Two babes have a long piece of cloth & are dragging it back & forth over the toe of the shoe.

For Shine (1942) the stage is set with a gigantic shoe on a pedestal. Two babes have a long piece of cloth & are dragging it back & forth over the toe of the shoe.

Comedian & dancer "Nicodemus" (Nick Stewart) is sitting up there inside the shoe smoking a cigar, not Louis thank god, Louis has got a dignified position in front of the band conducting. He sings this lyric, given in its entirety with Louis's slight revisions to the published lyric:

"Just because my hair is curly/ Just because my teeth are pearly/ Or just because I always wear a smile/ Like to dress up in the latest style/ Just because I'm glad I'm livin'/ Take my troubles all with a smile/ Just because my color shade makes no difference maybe/ That's why they call me Shine."

Written in 1910 by Cecil Mack, Lew Brown & Ford Dabney, the song has been regarded by some as moderately racist in its stereotyping, about a "happy" negro glad to be called Shine, a name whites typically imposed on anyone with glistening black skin, subservient smile, & eagerness to shine your shoes for a dime.

Ry Cooder added a new introductory lyric about being called "Sambo" "Rastus" & "Chocolate Drop," providing a context that gives the rest of the song with the original lyrics socially aware. Ry Cooder added a new introductory lyric about being called "Sambo" "Rastus" & "Chocolate Drop," providing a context that gives the rest of the song with the original lyrics socially aware.

But to those in the know, even in 1910 "Shine" may have been secretly subversive, as it was reputedly written about a real man named Shine who was beaten near to death during the Jim Crow Race Riots in New York City in 1900.

When Louis sang "Shine" in 1932's Rhapsody in Black & Blue he was dressed up in a foolish jungle outfit, & he did the number with the original lyrics intact.

This was a big hit for him at the time, but he certainly was a ware of the song as controversial, & in the 1942 variant, there are a couple word-changes in this performance. The original doesn't speak of skin color as making "no difference," & Louis has dropped the opening line about being a chocolate drop.

The guy with the cigar has meanwhile come down from the shoe & three beautiful girls are getting shoeshines from children, a girl & two boys. Mr. Cigar then rushes over to Louis to mug at him & do a momentary funny dance as Louis shoots for the high notes at the end of his trumpet solo.

An elaborately staged soundie, When It's Sleep Time Down South (1942) shows a dock with Louis Armstrong's pals relaxed, napping, or fishing off the edge.

An elaborately staged soundie, When It's Sleep Time Down South (1942) shows a dock with Louis Armstrong's pals relaxed, napping, or fishing off the edge.

Louis in a plaid shirt & sunhat is the only lively presence, sitting above the rest singing. At first, the musical instruments we can hear are not in evidence.

He gives the song a subdued bluesy treatment. Two sleepy children rouse themselves for a slow-motion softshoe.

Cut momentarily to footage of a passing riverboat, then "Nicodemus" is seen dressed in his best worn-out suit, relaxing on a dock, & he seems to be flirting with a mammy figure (Louis's singer Velma Middleton, but she doesn't sing in this one) who was looking after the two dancing children.

Velma has some fried chicken in a basket & when Nicodemus gets a bite of that, he starts a slow comic dance of pleasure, still eating that chicken leg as he makes his moves, as Louis does a horn solo. Velma has some fried chicken in a basket & when Nicodemus gets a bite of that, he starts a slow comic dance of pleasure, still eating that chicken leg as he makes his moves, as Louis does a horn solo.

Other members of the band suddenly have their instruments as well.

As the number winds down, the few characters on the stage who'd been roused to the music settle back into the sleepy-time mood.

Overlooking the stereotyping which the lyrics pretty much demand, this is in the main a wonderful soundie with a Romanticist edge. I mean, imagine a summer day when you can laze along a dock on the river with all your best beloved family & friends & Louis Armstrong performing for you, what a dream.

I'll Be Glad When You're Dead You Rascal You (1942) is shot on the same set as for Shine & Swingin' on Nothin' but without the shoe that Nicodemus sat in smoking his cigar, & with the honkin' big cut-out of a trumpet moved to the back of the orchestra.

I'll Be Glad When You're Dead You Rascal You (1942) is shot on the same set as for Shine & Swingin' on Nothin' but without the shoe that Nicodemus sat in smoking his cigar, & with the honkin' big cut-out of a trumpet moved to the back of the orchestra.

Director Josef Berne used a unique set only for Sleepy Time Down South. The four Armstrong soundies were released between May & August of '42, , but all were shot in a single day.

Louis received $5,000 for the day's work, presumedly including even pre-recording vocals immediately before filming, which was usually done on two different days. These would be the only soundies he'd ever make.

as I'll Be Glad begins, Velma Middleton can be seen sitting quietly on stage next to Louis' guitarist, Lawrence Lucie. We get a close-up of her while Louis does a rap-introduction to the number, establishing that the song is about the guitarist messin' with Louis's woman. Indeed Lawrence & Velma start hugging & looking at one another all moony-eyed as Louis sings:

"I'll be glad when you're dead you rascal you/ I'll be glad when you're dead you rascal you/ Now I brought you into my home/ You wouldn't leave my wife alone/ I'll be glad when you're dead you rascal you."

Pianist Luis Russell gets a a comedy moment when he stops playing & starts reading the newspaper. He's reading an article about Hitler, Mussolini, & Hirohito, which are the actual rascals Louis'd be glad to see dead.

Velma doesn't sing, but she does come down from the stage during Louis's horn solo & she dances up a storm, quite a display of athleticism for such a large woman. And she keeps it up through the next verse, though she doesn't do the rolling-on-the-floor breakdance which she does in Swingin' on Nothin'.

I suspect you can tell from this discription that this is great, amusing soundie overall. Louis had been filmed at Fleischer Studio many years earlier singing the same song, but it was used in a racist context of Louis being an African cannibal, in the Betty Boop cartoon I'll Be Glad When You're Dead You Rascal You (1932).

In 1933 Louis Armstrong was robbed by his manager Johnny Collins while touring in England, & was pretty much stranded. British orchestra leader Jack Hylton came to his assistance, arranging a tour of Scandinavia.

In 1933 Louis Armstrong was robbed by his manager Johnny Collins while touring in England, & was pretty much stranded. British orchestra leader Jack Hylton came to his assistance, arranging a tour of Scandinavia.

While in Copenhagen, Louis was booked into a vaudeville review, where some of the earliest film footage of his performances was made; only the live footage incorporated into the ultra-embarrassing cannibals-chase-Betty-Boop cartoon I'll Be Glad When You're Dead You Rascal You (1932) & the somewhat embarrassing jungle dream-kingdom musical short Rhapsody in Black & Blue (1932) are earlier.

Louis had already been a major influence on jazz musicians who would years later & for decades to come maintain that Louis invented modern jazz & was a primary influence on just everyone. When you hear his early recordings, those claims in his behalf are surely credible. But it's the rare chance to see his stage presence, which not too surprisingly turns out to rise well above the remarkable.

Three clips are in circulation from this performance. For Tiger Rag (1933) he speaks into the microphone noting this is a song every musician in the world likes to play, & his band behind him takes off with a pure dixieland ragt performance, nothing updated, it's total ragtime, retro even in 1933.

Louis stands with his horn & his handkerchief absorbed by his band's performance. Momentarily, he addresses the audience, "Now ladies & gentlemen, we're going to take a little trip through the jungle."

After a little rap about all of us helping to catch that rascally tiger, he begins his trumpet solo, & it's no longer pure ragtime but pure, brilliant, amazing jazz. After a little rap about all of us helping to catch that rascally tiger, he begins his trumpet solo, & it's no longer pure ragtime but pure, brilliant, amazing jazz.

I Cover the Waterfront (1933) begins with Louis walking center stage to the mic in front of the band, announcing the number, "Hello ladies & gentlemen, I'm Mr. Armstrong, & we're going to swing one of the good old good ones for ya, a beautiful numba I Cover the Waterfront, I Cover the Waterfront, I like it!"

Louis sings it with such style & beauty with little scat-bits tossed in, it's just so damned good it makes one's draw drop in awe. He's wearing a suit & bow-tie & is such a beautiful physical presence, singing mostly with his eyes closed. As if all that weren't treat enough, he quite naturally goes into his horn solo for close.

The third clip from this variety show is Dinah (1933). Once again Louis's band is giving a fairly "straight" Dixieland ragtime backup, but Louis sings none of it straight, scatting from start to finish of his wild vocalization. Then up comes his handkerchief & trumpet & he just rules the stage doing no more than standing still playing.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Velma was one of the great vocal talents of her era, & just about every working orchestra would have a female vocalist with them on the road for at least a few songs.

Velma was one of the great vocal talents of her era, & just about every working orchestra would have a female vocalist with them on the road for at least a few songs.

Ry Cooder added a new introductory lyric about being called "Sambo" "Rastus" & "Chocolate Drop," providing a context that gives the rest of the song with the original lyrics socially aware.

Ry Cooder added a new introductory lyric about being called "Sambo" "Rastus" & "Chocolate Drop," providing a context that gives the rest of the song with the original lyrics socially aware.

Velma has some fried chicken in a basket & when Nicodemus gets a bite of that, he starts a slow comic dance of pleasure, still eating that chicken leg as he makes his moves, as Louis does a horn solo.

Velma has some fried chicken in a basket & when Nicodemus gets a bite of that, he starts a slow comic dance of pleasure, still eating that chicken leg as he makes his moves, as Louis does a horn solo.

After a little rap about all of us helping to catch that rascally tiger, he begins his trumpet solo, & it's no longer pure ragtime but pure, brilliant, amazing jazz.

After a little rap about all of us helping to catch that rascally tiger, he begins his trumpet solo, & it's no longer pure ragtime but pure, brilliant, amazing jazz.