Proof of a Man (Ningen no shomei, 1977) has the tone & feel of an "issue of the week" telefilm & not even a good example of that.

Proof of a Man (Ningen no shomei, 1977) has the tone & feel of an "issue of the week" telefilm & not even a good example of that.

I saw this interacial murder mystery in the Japanese edit, but there is also a dubbed version re-edited for Caucasian audiences (with more scenes set in New York, & some scenes in Japan shortened).

American audiences really didn't want to see it because George Kennedy & Broderick Crawford as police detectives were not big draws. The big draw even for white folks would've been Toshiro Mifune, & his cameo was shortened by half.

The story is downright stupid but it has resonated in Japan as a bestselling novel, this allegedly classic film, & a television mini-series Proof of Humanity (Ningen no shomei, 2002) with an impressive cast headed by Ken Watanabe, & directed by Satoshi Isaka, & Takenouchi Yutaka as the young man seeking his Japanese mother. The story is downright stupid but it has resonated in Japan as a bestselling novel, this allegedly classic film, & a television mini-series Proof of Humanity (Ningen no shomei, 2002) with an impressive cast headed by Ken Watanabe, & directed by Satoshi Isaka, & Takenouchi Yutaka as the young man seeking his Japanese mother.

The "old straw hat" of the story can alone reduce the oversensitive to tears, when you'd think anyone with a lick of sense would be shaking their head in bewilderment that anyone believed the story was worth telling even once, let alone repeatedly.

In the 1977 film, a young black man, Johnny (pop singer Joe Yamanaka, who isn't black), shouts to a friend in a crowded street, seemingly in his native English, "Kiss me!" But he's actually saying he's going to Kisume, & this will soon be a rather silly "clue" that takes way too long to decode.

Johnny's soon murdered in Tokyo. He leaves behind a tattered straw hat that he brought with him from Harlem, for what reason is another clue, & a book of poetry.

Detective Munesue (Yasuka Tatsuda) has added up the slim "mystery" & speculates that Johnny was half Japanese, that his father may have been a negro soldier of the Occupation. If so, the kid must have come to the country to track down his mother (Mariko Okada). Well sure, I can see that in a book of poetry & an old straw hat.

Munesue heads off to New York city pursing the matter. He meets Detective Ken Shuftan (George Kennedy) who has figured out that Johnny's father committed suicide by getting himself run over by a car, specifically so that his son could get some insurance money to pay for a trip to Japan.

Many things have already gone wrong with the film. A minor point is that Johnny, supposedly an American kid raised in Harlem, can't speak English. Second, suicide may have all sorts of positive meanings in Japan, but in America, a black father (any father) who threw himself in front of an automobile so his kid could have the insurance money for a vacation would not only be a louse to pretend he was killing himself for his son's sake, but no insurance company would bother to pay it.

Besides, a trip to Japan may be hard for a Harlem kid to afford, but I'm sure Johnny could've saved enough even if only by flipping burgers to earn airfare & a guidebook undoubtedly available in the 70s, Japan on Five Dollars a Day.

Excuses can be made for the plot if the viewer wants to bother to think up rationales. But don't expect it ever to reach a point where even more excuses & rationales aren't required.

When this film was made the issue of half-American war babies having grown up as outcasts in Japan still had a lot of currency. The novel & the film were what passed, in Japan, for "liberal" on the issue. When this film was made the issue of half-American war babies having grown up as outcasts in Japan still had a lot of currency. The novel & the film were what passed, in Japan, for "liberal" on the issue.

Because of the number of GIs still in Okinawa to this day, the issues remain somewhat current, but it was that first generation of children regarded as the bastards of the enemy that got the worst of the worst treatment by society.

Now it wasn't always a worst case scenerio for those kids. My Uncle Wesley had a daughter in Japan & he was one of the rare Occupation soldiers who paid support over the years & went to Japan at least once a year (as a Merchant Marine) to visit his daughter, & proudly displayed her school photos at home.

My half-Japanese cousin had an okay life with her devoted mom, a reasonable education, a fairly good relationship with her American dad, & got to come & visit with her American family at long intervals. That her mom never married doubtless was do to having had a half-white daughter by an Occupation soldier, but at least life wasn't hell.

Sometimes the war babies were indeed abandoned by their moms out of shame & social stigma; the Elizabeth Saunders' Home was the most famous of several orphanages for such children. It was vastly more standard that the American dads did the abandoning, forced to do so or fascilitated in doing so by the American military government that gave the fathers no options.

Most often the mothers did everything they could for their children without assistance from society at large. For those who could not find options, & for some the poverty insurmountable, oyako-shinju (parent-child suicide) was a frequent alternative

But some mothers became activists in behalf of these children. For instance, the School for Amerasian Children in Okinawa was founded by mothers who could not bare the bad education & mistreatment their children experienced in the Japanese school system. They overlooked their own stigmatized condition to assist their children, & the Japanese government responded by refusing to recognize the education certificates of these children for the next twenty years.

Such children grew up under considerable discrimination. The government made it very difficult for Americans to adopt these kids, though in Korea half-Korean babies were being adopted to America left & right. Some Amerasians in Japan upon reaching their teen years ended up in the sex trade where their exoticism had a cash value, lending to further stereotyping of all Amerasians as the cause rather than the victims of a larger social problem.

Called ainiko, a derogatory term alluding to mixed blood, most were marginalized in nowhere jobs, frequently unable to marry. Some as young adults found their way to America where they would not suffer quite such persistent discrimination.

It wasn't emotionally likely that the reason a novel or film like Proof of a Man could never look at the marginalization & discrimination of Amerasians in any factual or sensible context, was because it would not be as "entertaining." Instead, it was preferable to sentimentalize an imaginary Amerasian as overwhelmed with filial love even though raised in a country where these strongly Japanese tropes have less meaning.

He also had to be raised in America not because that's particularly logical (it's not) but because it shunts aside the serious issues of how Amerasians have been treated in their native Japan. The story gets to have a "cute puppy dog" take on a topic that isn't cute at all, by doing away with all the authentic issues in favor of an inauthentic fable.

So, we have a soldier from Harlem who brought his illegitimate child home with him, though the military government wouldn't've permitted that to happen, nor was the Japanese government willing to part with even their most outcast citizens. The Occupation era Amerasians who did grow up in America usually came with their moms, not their dads. So, we have a soldier from Harlem who brought his illegitimate child home with him, though the military government wouldn't've permitted that to happen, nor was the Japanese government willing to part with even their most outcast citizens. The Occupation era Amerasians who did grow up in America usually came with their moms, not their dads.

But all sorts of variation must've existed, one way or another, & here again we just have to make up any old excuse or rationale to keep the story in play.

The origin of the "old straw hat," & what had happened to his mother after the war (successful fashion designer, married a politician, & no one knew about her life during the Occupation), is high melodrama very hard to find at all credible.

The resolution of this alleged "mystery" could be blamed on an idiotic script (by Zenzo Matsuyama) or on the bestselling novel by Seiichi Morimura. It would more accurately be blamed on the public's lack of taste in both novels & movies, & the public's desire to look at important issues in ways that are entertaining rather than realistic. The film is a three hanky weeper & that's enough. It "presses buttons" of cultural assumptons & attitudes without addressing the realities. It knocks the stuffing out of its own straw dogs.

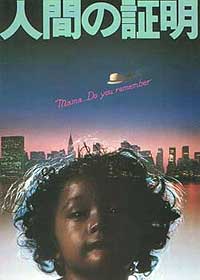

There's a theme song sung by Joe Yamanaka in broken English, "Mama, do you remembwuh, that old stuwah hat you gibu me." It's such a tear-wringing hoot to hear that crappy-ass song that it's almost worth sitting through a long crummy mystery just for the diddy.

It's probably not worth tracking down a copy of this film, but if you do, watch for the police lieutenant Shibue. That's Kinji Fukasaku, much better known as a yakuza film director than as a bit player.

There's no accounting for popular taste but this story's so foolishly popular someone thought it worth remaking as a dramatic mini-series.

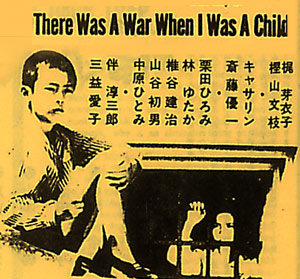

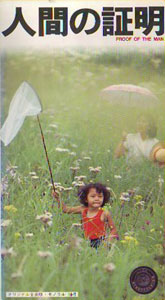

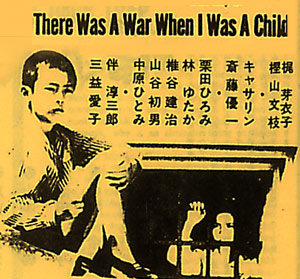

Another film to address the issue of half-American children of the war is the sensitive art film There was a War When I was a Child (Kodomo no koro senso ga atta, Shochiku Bunko, 1981). Though released a mite late, it was produced in honor of UNESCO's 1979 International Year of the Child. Another film to address the issue of half-American children of the war is the sensitive art film There was a War When I was a Child (Kodomo no koro senso ga atta, Shochiku Bunko, 1981). Though released a mite late, it was produced in honor of UNESCO's 1979 International Year of the Child.

It received a number of awards on the film festival circuit, including being grand prize winner at the Salerno International Film Festival & Manila International Film Festival. But then it pretty much vanished from film fan awareness.

I saw it at its 1982 Seattle premiere at the Toyo Cinema on a double-bill with a revival of Daisan no kagemusha (The Third Shadow, 1963), & though I've been able to see that samurai film again (available subtitled on the dvd "grey market"), I have not had the chance to update my viewing of the modern anti-war film. So I have only my old viewing-diary notes to remind me of it.

Reminiscent of Forbidden Games (Jeux Interdits, 1952), There was a War When I was a Child introduced one-name child-actress "Catherine" (or Kyasarin) in what seems to be her only film.

She plays the role of Emi, a half-Japanese girl whose father was an American. Emi's story is told from the point of view of a cousin, Taro (Yuichi Saito).

Toward the end of the WWII, Taro & his mother Kazue (Fumie Kashiyama) leave Tokyo, which the Americans have been fire-bombing. They retreat to safety in Northern Japan to stay with Taro's grandmother (Hiromi Nakahara) & two aunties (Meiko Kaji as Futae & Aiko Mimasu as Miyo) who run a bean-curd tofu company while men are off to war.

His grandmother tells him never to go in the barn, because it is haunted, so of course he checks it out & discovers Emi, Aunt Futae's hidden daughter. As her father was the enemy, Emi is at risk of being taken away by the authorities, so the women protect her & hide her existence, never having registered her birth so that she does not legally exist.

Taro deeply hates the enemy due to his susceptibility to the xenophobic tone of the era & having been taught that whoever does not hate Americans cannot love Japan, & who can blame anyone at a time when Tokyo was being burned down from one end to the other in an intentional policy of "kill as many civillians as possible!" But his friendship with Emi breaks down his prejudice, in an idyllic countryside beautifully photographed.

Sentimentality does mar the film, but taking the childrens' point of view, it has its terrifying moments as the children bond & play always at risk of the villagers spotting Emi & reporting her existence to the police. The film truly merits being dredged up from its present obscurity & given new life in the international marketplace on dvd.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

The story is downright stupid but it has resonated in Japan as a bestselling novel, this allegedly classic film, & a television mini-series Proof of Humanity (Ningen no shomei, 2002) with an impressive cast headed by Ken Watanabe, & directed by Satoshi Isaka, & Takenouchi Yutaka as the young man seeking his Japanese mother.

The story is downright stupid but it has resonated in Japan as a bestselling novel, this allegedly classic film, & a television mini-series Proof of Humanity (Ningen no shomei, 2002) with an impressive cast headed by Ken Watanabe, & directed by Satoshi Isaka, & Takenouchi Yutaka as the young man seeking his Japanese mother.