Akira Kurosawa's first family drama about the psychological damage that followed the bombing of Nagasaki was I Live in Fear (aka Record of a Living Being, 1955) with a youngish Toshiro Mifune playing a neurotic old man who wants to get the hell out of Japan before it's vaporized. Decades later when Kurosawa was himself a neurotic old man, he began revisiting old themes, although without new insights.

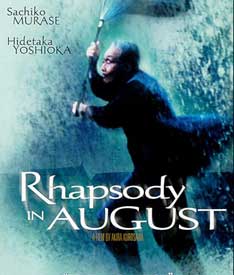

In Madadayo, an eccentric professor loses his Tokyo home to American bombs. In Rhapsody in August, an extremely elderly grandmother, half-bald because of exposure to radiation, lost her husband to the bombing of Nagasaki. Lo these many years later her entire family speculates endlessly about how the bomb changed her life.

Madadayo with its old man & Rhapsody in August with its old woman seem to be companion pieces expressing how Kurosawa thought the elderly either are or should be perceived. Rhapsody is the better of two poor films, because the old man was actually an appalling bore, whereas the old woman was a great storyteller in her own right & cute as a button. When granny tells a story to her four grandchildren, & they respond to it by looking around the rural environment for evidence & locations of family history & lore, the film almost becomes magical. Unfortunately this element merely decorates an otherwise pisspoor film that often seems like an long editorial on H-bombs & the generation gap. It is so static that it occasionally feels like an essay on these subjects merely posing as fiction.

Ultimately both films are dull even if the central figure is Rhapsody is in herself more interesting. Most of the time we see the old woman's grandchildren & sundry relatives sitting around talking about grandma or about the atomic bomb or about grandpa who died with a school full of children in the middle of Nagasaki, the subtext being that there were no such things as Japanese soldiers or war-workers in Japan, but only innocent school teachers & wee sweet kids. The intrusion late in the story of Richard Gere (a repulsive actor frankly) as the gentle apologetic ultra-respectful geeky American fukwit relative only enhanced the film's tedium.

The script & the film that rose from it come off as an old man lecturing younger Japanese to remember how Japan suffered but to forgive those terrible tormentors the Americans, but do not ever dare to ask anyone to remember how, say, China or the Philippines suffered thanks to Japan, & don't ever express the least apology toward anyone Japan injured. Kurosawa's woe-is-me posturing approaches being churlish; it is certainlyh self-justifying & phony. Instead of confronting the fact that atrocities breed further atrocities, Kurosawa posits an innocent Japan void of responsibility.

His script makes him seem like a whining right-wing son-of-a-bitch who wishes everyone still worshipped the Emperor, lamenting a lost age when having a personal samurai heritage like Kurosawa's would've permitted him to legally test his sword by cutting down unarmed peasants should that need arise, but please don't let that samurai ever be afflicted by the physical & emotional pain of actual repurcussions. Kurosawa's whining lacks moral complexity; he really seems to believe "forgiving" America for something horrendous means more than confessing to any level of Japanese responsibility. His approach is ultimnately a whitewash that in the name of "remembering" & "forgiving" actually forgets nine-tenths of all that matters for apology.

There are too many moronic messages in this film. The message that Japan still hurts from being bombed is a fair one. But expounding on it ad nauseum & eventually preaching the forgiveness of America because War & not Americans caused such pain, sheesh, the sheer neurosis of the script cannot be hidden by putting all this blather in the mouths of a cute old lady or her grandchildren or in the mouth of a govelling wuss of an American relative. These characters are not distinct; they are Kurosawa's voice exclusively. Despite so many characters sitting around being talking-heads for what feels like hours & hours, only one idea from one character is actually expressed, & that character is Kurosawa behind the camera.

Without even token acknowledgement of Japan's role in its own injury, the film is merely dishonest, a dishonesty not remedied by being so damned sentimental about old age. Masaki Kobayashi in his epic masterpiece The Human Condition looks honestly at Japan's crimes in Asia. Kon Ichikawa's spiritually dynamic Harp of Burma is an angst-ridden poem for peace expressed in a war-savaged landscape. Japanese directors have made some of the most powerful anti-war films ever made, but self-awareness is always distinctly missing from Kurosawa, & in this signal area of Japanese cinema, he never contributed even one film of value. And that's pretty painful to say of one of the world's cinematic masters.

Comparing Kurosawa's whining about the physical & psychological damage to Japan to his superb romanticizations of medieval warfare & swordplay makes one wonder if he ever matured spiritually or intellectually. He seems never to have realized that a world where the samurai class could kill any peasant merely to test a sword is not superior to a world in which would-be conquerors get their arses burnt. Rhapsody of August reveals a terrible limitation in Kurosawa's own human condition. But we must nevertheless honor him for having made some of the world's greatest films -- long before he got round to the twaddlingly politicized sentimentality of Rhapsody in August.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|