The seventeenth feature film about Zatoichi the blind masseur & quick-draw swordman is Zatoichi Challenged (Zatoichi chikemurai kaido, literally "Zatoichi's Spurting Blood Road," Daiei, 1967). The seventeenth feature film about Zatoichi the blind masseur & quick-draw swordman is Zatoichi Challenged (Zatoichi chikemurai kaido, literally "Zatoichi's Spurting Blood Road," Daiei, 1967).

It incorporates some elements of the "singing samurai" or musical chambara subgenre, as Ichi travels with a troupe of performers who enjoy singing along the way.

Pop singer Mie Nakoa plays Miyuki, one of the singers among the travellers. Mie made a shortlived attempt to reach the popsong market in the United States during the British Invasion, doubtless hoping for a Japanese invasion.

She made an appearance on an episode of the 1966 musical variety series Where the Action Is that regularly featured Paul Revere & the Raiders & top-ten pop stars.

The attempt to make a new hit covering Kyu Sakamoto's 1963 international chart-topper "Sukiyaki" really didn't go over, although in Japan she did make a successful transition from young pop singer to television actress.

Shintaro Katsu as Ichi also sings a good yakuza-enka (gangster folksong) in this episode, & he was deservedly a popular enka singer as well as actor. Shintaro Katsu as Ichi also sings a good yakuza-enka (gangster folksong) in this episode, & he was deservedly a popular enka singer as well as actor.

There's plenty of comedy, such as defeating a woman boss by using the iai quickdraw sword to shave her eyebrows off. But as always there's seriousness to the plot.

Pornographers have taken captive a timid artist, Shokichi (Takao Ito), forcing him to make shunga prints to pay gambling debts. After the death of a young mother, Ichi becomes the protector of her little boy Ryota & takes him on the road to find his father, who turns out to be the unwilling porno artist.

Jushiro Konoe plays Tajuro Akatsuka, a generally kind & incredibly intense samurai, but also a shogunate undercover investigator of crime who appears to be devoid of any capacity to forgive criminality.

Konoe had been a leading man earlier in his career & was still getting important roles through the 1960s, having aged into a wonderful character actor with a powerful screen presence similar to that of Toshiro Mifune. Konoe had been a leading man earlier in his career & was still getting important roles through the 1960s, having aged into a wonderful character actor with a powerful screen presence similar to that of Toshiro Mifune.

Tajuro has been sent on a mission that pretty much requires him to kill everyone involved in the manufacture of banned pornography.

This puts Ichi in a difficult position trying to unite the boy with the father, as he would rather not have Tajuro as an enemy. When they inevitably clash, it's one of the greatest duels in the entire series, choreographed for poetic, emotional effect.

When Ichi tosses his sword like a spear in order to save the boy's father from Tajuro's henchman, he's left momentarily unarmed, & Tajuro could have killed him.

But Tajuro holds back due to Ichi's purity, leaving everyone alive, in spite of our expectations from his unyielding sternness. But Tajuro holds back due to Ichi's purity, leaving everyone alive, in spite of our expectations from his unyielding sternness.

This is simply a great moment in the story, with an implication that Tajuro & Ichi might meet again someday, & a rare moment when Ichi is able escape at least one cause for his personal overwhelming burden of guilt.

There's a sad fillip to the story as Ichi hides from the boy, who liked Ichi better than his never-known father. Both part in tears.

Zatoichi Challenged began with a script that was merely adequate but with fine acting, with Katsu's comfortable performance as the humble nurturing hero, with splendid fight choreography & gorgeous cinematography & the important role of Jushiro Konoe in the fine cast. It comes together as a better film than the workmanlike script alone could provide.

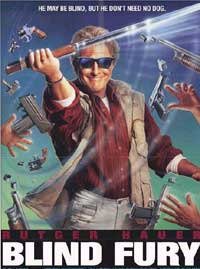

Blind Fury (1989) was revised from Ryozo Kasahara's screenplay for Zatoichi Challenged. It fails for several reasons, starting off with the modern setting that provides just about everyone except Nick Parker (Rutger Hauer) with a gun. Blind swordman action vs bullets is not as convincing as quick-draw swordplay vs sword. Blind Fury (1989) was revised from Ryozo Kasahara's screenplay for Zatoichi Challenged. It fails for several reasons, starting off with the modern setting that provides just about everyone except Nick Parker (Rutger Hauer) with a gun. Blind swordman action vs bullets is not as convincing as quick-draw swordplay vs sword.

Rutger as Nick is too handsome & studly to be convincing as an underdog sort of hero. He walks through the role posturing like a big tough hero rather than a blind guy easily mistaken for helpless but who is unexpectedly powerful.

The script as adapted by Charles Robert Corner changes just about everything & is crammed with hamfisted comedy (blind man driving car in standard car chase, for example, & proving himself a better trick driver than the sighted, is not an interesting substitute either for swordplay action or human comedy). The reliance on humor approaches slapstick & has the effect of further undermining an already unbelievable character, making the absurd ridiculous instead of credible.

There is no western equivalent of the tradition of wandering blind masseurs, so Nick's history bears almost no relationship to Ichi's, & his reasons for tapping his way along the highway margins are not as well grounded. Nick was blinded in Vietnam after his best friend (Terry O'Quinn) abandoned him to the enemy. Vietnamese villagers saved his life & quickly taught him to be a great swordmaster though blind. Too bad this wasn't the only unconvincing bit in the film!

Twenty years later he finds himself in the way of helping out a boy (Brandon Call) whose mother (Meg Foster) has just died. Nick must get the boy to his wayward father, who happens to be the same guy who proved to be such a coward in Vietnam.

His old pal presently works, against his will, for mobsters, making a designer drug that has the appearance of bright blue bath crystals. His old pal presently works, against his will, for mobsters, making a designer drug that has the appearance of bright blue bath crystals.

So Nick has to save his old pal from the mob while protecting the child from would-be kidnappers & reuniting son & father. When they all get in a very sticky situation, his fellow veteran has a choice to make, run like hell as he had done in Vietnam, or redeem himself for past cowardice.

The bad guy hires a Japanese assassin played by Sho "American Ninja" Kosugi. With Kosugi's aid we are treated to the film's only significant duel, which isn't awful, though Kosugi is so obviously more skilled than Hauer it's not believable when Nick wins. Kosugi's character is also very poorly integrated into the story, so a tale already having trouble finding any place of conviction is only further strained by this last-ditch effort to retain a climactic duel for what was originally a swordplay film.

At every point where the two films might be compared, the remake is not just a little worse, but resoundingly inferior. Concocting a box of blue crystals in a mob lab is not as interesting as an artist forced to create illegal block prints, & the lab being right next to the casino mobster's penthouse isn't even distantly likely.

So too in the original there is pathos & honor when the samurai & Ichi have their final incredible duel between men who know & like each other, but Sho Kosugi is hardly more than a tacked-on character who runs in at the last minute, jumps around for a while with flashings katana, then basically trips & kills himself. If Sho Kosugi had played a character rather bigger than Nameless Assassin & had had a relationship with Nick similar to that between Katsu & Konoe in Zatoichi Challenged, the final duel might've had emotional power. As it stands, it's merely phony.

I'm sure Blind Fury will be more impressive to anyone who hadn't seen Shintaro Katsu making the idea of a blind swordsman totally credible. Blind Fury begs the viewer to overlook too much that is idiotic, whereas the original convinces the viewer it isn't idiotic at all.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Shintaro Katsu as Ichi also sings a good yakuza-enka (gangster folksong) in this episode, & he was deservedly a popular enka singer as well as actor.

Shintaro Katsu as Ichi also sings a good yakuza-enka (gangster folksong) in this episode, & he was deservedly a popular enka singer as well as actor. Konoe had been a leading man earlier in his career & was still getting important roles through the 1960s, having aged into a wonderful character actor with a powerful screen presence similar to that of Toshiro Mifune.

Konoe had been a leading man earlier in his career & was still getting important roles through the 1960s, having aged into a wonderful character actor with a powerful screen presence similar to that of Toshiro Mifune. But Tajuro holds back due to Ichi's purity, leaving everyone alive, in spite of our expectations from his unyielding sternness.

But Tajuro holds back due to Ichi's purity, leaving everyone alive, in spite of our expectations from his unyielding sternness.

His old pal presently works, against his will, for mobsters, making a designer drug that has the appearance of bright blue bath crystals.

His old pal presently works, against his will, for mobsters, making a designer drug that has the appearance of bright blue bath crystals.