One of the standard features of medieval yakuza films is gang warfare, which provides a fine excuse for battles to occur even in the largely peaceful Tokugawa Era. These highly localized wars were typically over territory to decide who gets to run gambling enterprises & prostitution, to exterminate a rival & expand one's territory.

There were in effect two kinds of kyokaku or "town knights" as the medieval yakuza likened themselves. Both types were organized into gangs or protection-societies. The hatamoto-yakko were answerable to a gambling-boss; the machi-yakko were answerable to the labor boss.

At first glimpse, the labor boss (oyabun) is a good-guy like a labor union president who provides useful & legal employment for his men (who lose their incomes gambling). Meanwhile the gamblers' oyabun is a bad-guy hiring henchmen to keep the gambling, extortion, & prostitution going full-blast. At first glimpse, the labor boss (oyabun) is a good-guy like a labor union president who provides useful & legal employment for his men (who lose their incomes gambling). Meanwhile the gamblers' oyabun is a bad-guy hiring henchmen to keep the gambling, extortion, & prostitution going full-blast.

The machi-yakko arose specifically to oppose the excesses of the older hatamoto-yakko who had arisen initially as defense leagues against the overbearing military class. Yet the eventual development was that the legal enterprises became, too often, mere fronts for illegal enterprises.

One boss, then, was pretty much as shady as another boss. When & if a good oyabun arose, he might well be a gamblers' oyabun; & when a oyabun was a total son of a bitch, he might well be a thuggish contractor whose laborers were brutes.

Through this yakuza environment were a class of wanderers or toseinin who typically wore blue capes & flat-topped sedgehats & carried a single longsword. Some were ex-farmers whose farms had failed so had gone on the road as itinerant laborers. Others were free spirits, young men who adapted the kyokoku code of yakuza behavior & could be assured free lodging just about in any town where there was a yakuza organization.

One reason toseinin were so eagerly welcomed into the homes or headquarters of bosses was because of the aforementioned gang wars or smaller vendettas which called for extra men from to time. One reason toseinin were so eagerly welcomed into the homes or headquarters of bosses was because of the aforementioned gang wars or smaller vendettas which called for extra men from to time.

A wanderer who accepted a boss's hospitality was bound by the kyokaku code of yakuza behavior to defend that house against any foe, without question or wavering, & to obey the oyabun under any circumstance to balance out one's obligation for a meal & a night's lodging.

In cinematic presentations this easily led to a situation where a toseinin had accepted lodging only to find himself roused up in the middle of the night & forced to go assassinate someone. Obedience to the oyabun could not be questioned. So what looks at first like a freewheeling lifestyle becomes a dangerous one that can require even a good guy to do something quite terrible.

One of the conventional set-pieces of medieval yakuza films is a toseinin's arrival at a village boss's headquarters offering some inexpensive gift, such as a towel, as humble payment for a night's lodging. If the representative of the household accepts the gift, then no obligation for a night's lodging will be incurred. So the wanderer will push the towel toward the greeter & say, "Please take my humble gift," & the greeter pushes it back at the wanderer & with exaggerated graciousness says, "I couldn't think of taking any payment."

If unfamiliar with the fundamentals of yakuza fiction, this sort of sequence may seem pointless & merely delays the action. But once one understands the underlying meaning of this kind of recurring sequence, it becomes quite tense, as it is about acquiring or not acquiring obligation, & there's always the possibility that some decent fellow is going to be hoodwinked into becoming the fall-guy for a rotten gangster boss's dubious agenda.

Historically speaking the toseinin did not have to be an associate of yakuza though in fiction, at least, he almost always is. The same image of flat-topped sedgehat & blue & white peasant-cloth cape also belonged to wandering enka folksingers specializing in songs of chivalrous & tragic heroes. Such a wanderer might stay at yakuza headquarters along their route, or might prefer to stay at temples along with other sorts of actors & musicians & outcastes.

The enka toseinin is rarely seriously addressed in the cinema, though several films starring Hibari Misora assume the enka performer & the gambler toseinin are one & the same. Life of Chikuzan the Shamisan Player (Chikuzan hitori tabi, 1977) is a rare case of a seriously treated wandering folk performer film. Folksingers right to the present day play into this matatabi traditon.

Films about any sort of non-samurai wanderers around Japan, such as the Zatoichi series, can all be loosely categorized matabi-mono, but the central film type requires the specific costume of the toseinin.

The most extremely romanticized matatabi-mono may well be the family films of singer-actress Hibari Misora, in scores of films like Irowa wakashu furisode zakura (A Young Rabble, 1959) & Hibari no Mori no Ishimatsu (Ishimatsu the One-eyed Avenger, Toei, 1960).

At the opposite end of that extreme is the Mushuku-nin Mikogami or Trail of Blood trilogy (1972) starring Yoshio Harada as Jokichi, one of the most brutalized & brutal peasant avengers in all jidai-geki or chambara cinema. One of the oddest matatabi films are those about Kibakichi (2003, 2004) which duplicate the image of Jokichi then adds lycanthropy.

Between lighthearted Hibari films & the gruesome films about Jokichi, there is to be found at least one really great & thoughtful matatabi-mono that is simultanously blackly comical & realistic.

In Kon Ichikawa's The Wanderers (Matatabi, Toho, 1973), one young character is given hospitable welcome, then informed he must go kill somebody who is a threat to the yakuza house. Unfortunately, the "someone" is the young man's own father. In Kon Ichikawa's The Wanderers (Matatabi, Toho, 1973), one young character is given hospitable welcome, then informed he must go kill somebody who is a threat to the yakuza house. Unfortunately, the "someone" is the young man's own father.

In other films the victim is more apt to be a perfect stranger. The gambler who became a killer will have sympathy for the widowed wife or a daughter who becomes the love interest, or orphaned child who becomes a ward of the killer himself. This can lead to a desire to give support to survivors of the killing, but those survivors must refuse him, desiring no obligation toward someone they have every reason to despise.

While planning The Wanderers, Kon Ichikawa said it would be a story "about the tragedy of a very young outlaw." After the film's release, it was critically acclaimed as an anti-yakuza film (or anti-romantic yakuza), which at the tail-end of the ninkyo-eiga or chivalrous gangster film craze was something the critics liked to see lampooned.

Ichikawa himself never described it in "anti" terms but as his version if Easy Rider (1969). And for all its cruel black humor & its focus on the unluckiest of all gamblers, I find it nevertheless a highly romantic adventure film, one of the best films ever about toseinin. Ichikawa himself never described it in "anti" terms but as his version if Easy Rider (1969). And for all its cruel black humor & its focus on the unluckiest of all gamblers, I find it nevertheless a highly romantic adventure film, one of the best films ever about toseinin.

It's true, though, Ichikawa denies his three young heros much dignity as they bumble through the gamblers' world. He refuses to let even one of them die nobly if death is inescapable, & paints all three as comic victims of their ludicrous goals.

Yet there's not much slapstick in their failures. When one of them caught in a duel inside a building runs about wildly without skill gets his sword caught in an architectural beam, it's blackly humorous, but it's a tought spot to be in too. Ichikawa clearly has sympathy for his misguided, insecure young men, & despite how funny they can be, Ichikawa does not treat them as mere jokes.

The three young toseinin wander the countryside in a kind of apprenticeship to become strong yakuza. Or such is their preposterous intent. They are really just farm-boys without much skill or luck.

When with other toseinin they were hired by small-town bosses to pad out the numbers during gang wars, such foolish young men tended to look for others like themselves on the rival side of a battle, & cross swords in mock duels, looking busy without trying to injure one another. When with other toseinin they were hired by small-town bosses to pad out the numbers during gang wars, such foolish young men tended to look for others like themselves on the rival side of a battle, & cross swords in mock duels, looking busy without trying to injure one another.

Sometimes this plan failed & a young wanderer would find himself facing a genuine fencer. Our untrained heros Genta, Shinta, & Mokutaro (Ogura Ichiro, Bao Isao & Hagiwara Kenichi) have many close calls but manage never to fall in battle.

In the end, two of three meet the most miserably pathetic of ends. One is bitten by a harmless snake but the bite becomes infected & he dies raving of blood poisoning. Another slips & falls down a hillside busting open his head, & his remaining companion, who'd been taking a dump in tall grass, never figures out where his friend vanished to in an instant.

As the screen goes dark, we hear the one remaining toseinin call out one more time to his vanished friend. And it's a finale that can make you laugh through the tears for so much human folly.

Kon Ichikawa's Matatabi was by no means the first film to spoof the low-ranking wanderer seeking pursuing a peasant's equivalent of a samurai's training journey. Kon Ichikawa's Matatabi was by no means the first film to spoof the low-ranking wanderer seeking pursuing a peasant's equivalent of a samurai's training journey.

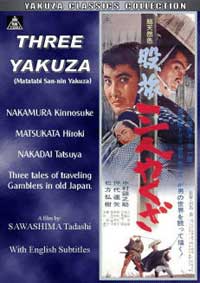

Kinnosuke Nakamura often starred in matatabi-mono, such as in the title role for Seki no Yatappe (Killer Yatappe, 1963), no comedy but very much a morality piece rather than purely romanticized. More overtly comical is Tadashi Sawashima's excellent anthology film Matatabi san-nin yakuza (Three Yakuza Tales, 1965). Kinnosuke plays a dorky toseinin apt to drop his sword in a fight.

Kinnosuke's dark comedy is the third of three matatabi-mono wanderer tales told. The first story, "Autumn," features Tatsuya Nakadai in a powerful little performance, in which he keeps about him a constant sense of profound sadness.

Splendid romantic imagery introduces the toseinin wanderer Sentaro (Nakadai). He is a wanted man; a price is on his head, dead or alive, for having killed two government officials. He arrives at a village yakuza headquarters, presenting himself in that beautiful mannered method of yakuza ritual greeting.

He's humbled by his needful condition, archly polite, & reluctant to reveal what skill he has. Yet legend preceeds him. Yakuza have been telling one another tales of how Sentaro took on several samurai at once & beat them. He's humbled by his needful condition, archly polite, & reluctant to reveal what skill he has. Yet legend preceeds him. Yakuza have been telling one another tales of how Sentaro took on several samurai at once & beat them.

Sentaro's newfound fame does not delight him, as there is no joy in being hunted for bounty. He was forced to kill a one-eyed bounty-hunter ronin along the road. The man was rough & horrible, but he had a girl's comb upon him, which Sentaro kept as reminder that even such a man as that had feelings & dreams.

Oine, a young woman caught in a loan-contract to be paid back through prostitution, has begun to rebel, as she's in love with an ex-samurai who has become a boatman, Innosuke, who wants to marry Oine. Innosuke has gone into hiding after having had attacked the yakuza who prostituted Oine. So Boss Kojiya wants the boatman found & killed.

Obligation for a night's lodging causes Sentaro, against his humane judgement, to harrass Oine into submission, as the oyabun requires. The imbalance of Humanity & Duty, of compassion for the innocent vs obedience to an oyabun (like unto a samurai to his lord), torments Sentaro's spirit.

Boss Kojiya's villainly makes life harsh for locals. Sentario feels guiltier & guiltier serving such an evil man, & feels pity for Oine. When eventually realizes the one-eyed ronin he killed along the road was in fact Innosuke trying to earn the bounty only to redeem Oine, Sentaro's overcome with depression, & confesses to Oine.

An ugly one-eyed man like that in love! And loved in return. And it came to this. The sadness is beyond baring. Sentaro's final decision to "do the right thing" lends a macabre beauty to the climactic one-against-all swordfight. Live or die, Sentaro no longer has to hate himself.

In the second tale, "Winter," a toseinin named Genta (Hiroki Matsukata) saves the life of an old man he calls Pops (Takashi Shimura) who was caught cheating in a gambling hall. It was no chivalrous act, as the toseinin expects some payment for having helped the old cheat escape. The storm about them is awful & they shelter at an empty country cottage.

To fill time waiting out the storm, Genta tells his story. He became a yakuza after having been cast out of his village like an unwanted dog after his indebted father committed suicide. He was only thirteen years old at the time & has been a wanderer since. To fill time waiting out the storm, Genta tells his story. He became a yakuza after having been cast out of his village like an unwanted dog after his indebted father committed suicide. He was only thirteen years old at the time & has been a wanderer since.

It had been his boyhood dream to be a farmer, for he loved good soil & watching stuff grow. He hoped to clear the debt on his father's land, but there were people interested in the property who were more clever than himself, & it really didn't matter what he did, the game was against him.

At first Gemta tried to find honest work, but failed, & ended up in the gangster world. Having lost his old dream of becoming a farmer, he now just wants Pops to teach him all the crooked dice tricks. The old man warns him he'll live a life of misery if he follows this road, steeped in the filth of yakuza without a decent life or a decent death.

A young girl, Omiyo (Junko Fuji), returns to the house & finds the young & old yakuza ensconced. It is no coincidence that the old man led Genta here, for he was seeking shelter from the storm somewhere he knew from a former time.

When Omiyo was little, that old man carved her a doll. Now she's a grown woman who still treasures that carving. Her mother Oharu is dead & she's now on her own. Though Genta is a scoundrel, he is slowly moved to sentiment.

As the story progresses, it is finally revealed that the old man is in fact Omiyo's father, aching to be forgiven. Learning that his wife is dead he can't beg her forgiveness. He can beg Omiye's, but this revelation makes her too angry to be leniant. When at last she relents & calls him father, Genta is deeply moved.

The yakuza from the gambling hall have not given up searching for the cheater with every intent of killing him. When they find the cottage, Genta strives to kill them all to save Pops & the girl so that someone in this awful world can live happily ever after. But their screaming triggers an avalanche on the mountainside above them, & the players in this little tragedy are erased from existence. The yakuza from the gambling hall have not given up searching for the cheater with every intent of killing him. When they find the cottage, Genta strives to kill them all to save Pops & the girl so that someone in this awful world can live happily ever after. But their screaming triggers an avalanche on the mountainside above them, & the players in this little tragedy are erased from existence.

In the final tale, "Spring," Kinnosuke Nakamura is introduced as the toseinin Kaze-no-Kyutaro, undecided which road to take, as he has no particular destination. He tossed his hat on the decision.

The headman of the next village unexpectedly offered Kyutaro lodging & a meal. Despite suspicions, he's soon stuffing himself with tanuki (badger) soup & sake. The village headman even implies that Kyutaro can do anything he pleases with the maid, who is a great beauty.

"Boss, how many men have you killed so far?" asks the village headman, for Kyutaro carries himself like one hell of a chivalrous guy in a fabulous wanderer outfit. Fact is, he just bought an outfit. But he takes advantage of the opportunity to fabricate a hero's history.

Once they have him under obligation for lodging & a meal, the villagers spring on him their wish for him to kill a man who has been terrorizing them. "Devil" Hanba has been preying on the locals, killing who displeases him, strongarming the rest for money.

Kinnosuke is so beautiful & innocent-looking in this role, which is at once comical & pathos-ridden. Kyutaro was enjoying posing as great, manly fellow, but really killing someone, really risking his life, that's a startling thing to ponder.

He tries to worm out of it with dignity, planning to run out never paying his debt of obligation. But they lean on his desire to be perceived as a ninkyo or chivalrous hero who troubles the strong in defense of the weak.

When he confronts Oni Hanbei, the villain cuts a butterfly out of the sky, & Kyutaro actually drops his sword in fright.

The cowardly villagers immediately begin wining & dining the next yakuza toseinin to come along. Kyutaro's indignant speech is great. But he has a crush on the orphan maiden the village abusively offers to wanderers. Her tears have moved him.

His duel with Oni Hanba is one of the most whimsically realistic displays of talentlessness ever put to film. But Kyutaro has a plan & leads the bad guy into a tanuki trap, & thereby wins the day. But far from feeling justified in having achieved his heroic dream, when he sees the maiden he fell for heading out of town, he casts off his symbols of a wandering gambler & runs after her as an honest citizen.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|